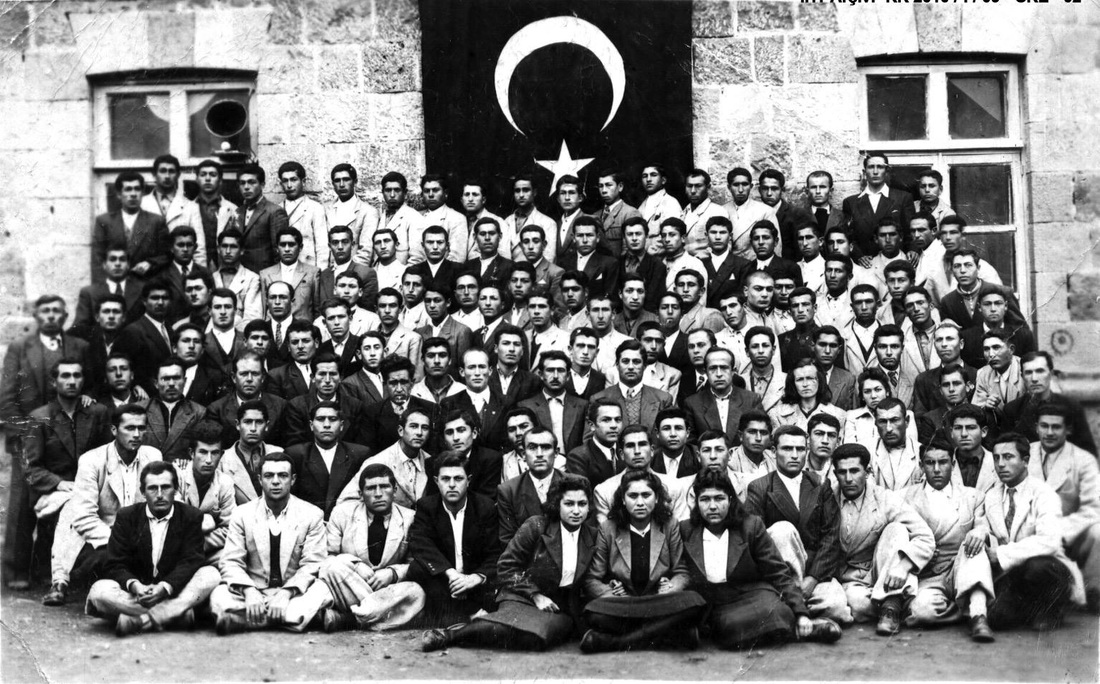

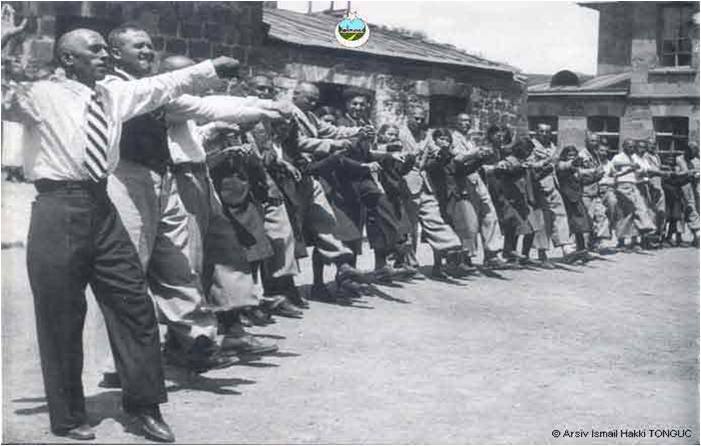

Village Institutes of the RepublicThe Village Institutes were founded upon egalitarian principles in 7 regions and 21 different locations across Turkey. The aim of these Institutes was to liberate villagers through education and culture and to provide a means to enlightenment for Anatolian villages, which were enduring middle-ages like conditions at the time, and through this to rejuvenate the whole country in the social, cultural and education spheres. In this sense the Village Institutes were a social transformation project. The education provided by these institutes utilized a secular, democratic and scientific curriculum with a student-centered pedagogy, which aimed to help participants realize their full human potential. Unfortunately, through a forced change in their curricula in 1947, Village Institutes were hollowed out and were then officially terminated in 1952. Widely accepted by academics and civil society institutions as having helped students develop and further all aspects of their potentials by bringing out and nurturing their creative strength through the application of learner focused, democratic and humanistic pedagogic principles, the Village Institute system with its focus on the person remains relevant to this date.

|